[INTERVIEW][10/04/25]Not Done Until I’m Done

a CONVERSATION with

Tracey Todd

Tracey Todd’s The Flavor of Cassava Leaf Over Rice (now streaming on MUBI) is a story of regret. Two old lovers—Michael and Fatima, both caught in the throes of crisis and dissatisfaction—reconnect in Los Angeles and spend a weekend together, investigating their relationship to each other, to their past lives and their current lives. Aaron Berry Davis sat down with Tracey Todd at The Alcove in Los Feliz, on a rainy LA day, to discuss the film. There are many spoilers, if you care about that sort of thing.

One of the first notes I took down when I re-watched Cassava Leaf yesterday was about the coyote sounds in the opening. The first time I watched it, that didn't stick out to me, but the second time I couldn't avoid it. It was interesting to me because the coyote is such an LA tarot card.

Tracey: I actually just saw a coyote when I was coming here, in Los Feliz. It was crossing the street right behind me. It was wild.

Why did you want to include the coyotes in there?

Tracey: You know, I honestly don't know. Yeah, I can't definitively point to why. I wanted to have this kind of surrealist element where there's something that's following the main character.

The thing that stuck out to me about it was the timing of the coyote howls. It’s when you’re setting up the world—Michael’s world—and the sound you chose is from a creature we typically think of as lonely. They're solitary, you know. They don't travel in packs.

Tracey: Mm-hmm.

And then, of course, the reason we see them in heavily populated areas like Los Feliz is because they've lost something. And, to me, that's Michael in the film. He's haunted by these things that he lost, things he's not sure he can get back, and he’s wandering LA like a coyote.

Tracey: You know, making any film or art, I would say there's an animating force to it where you're just unconscious. I definitely wanted Michael to be haunted, and for you to feel the haunting and the loneliness throughout.

Would you say your art comes from a conscious place or an unconscious place?

Tracey: I think it mostly comes from an unconscious place. I can't speak for anyone else, but I feel like I'm always thinking about things, whether it's things going on in my own life, things going on in the world, things going on in the country, things going on with my friends and my family. And I try to make sense of those things in my head as I'm just going about life. And they jumble around until they hit this kind of Tetris shape where they lock in. So I have an idea, and all of those things are present, and then they become present in a way where there's some organization and there's a narrative to it. It helps me deal with those issues that I didn't necessarily find any kind of resolve or reason for. But I can't speak to how or why it just. They jumble around and then they click in and I'm like, “Okay.”

What was the seed of the idea for Cassava Leaf?

Tracey: I think the seed of Cassava Leaf was me living in LA. Granted this is a fictionalization, but from my experienced I could understand living in Los Angeles and feeling this disconnect from the city. But also having an affinity for it as well. There’s this closeness, but also distance, to this place that I was living in. And then also there was this distance from a life that I believed I would live forever. Something that I feel like, yeah, perhaps was lost in a life on the East Coast. So I could get into the character's mind state of what does it feel like to kind of be stranded in paradise, so to speak.

So, why an author? Because that was the other thing that stuck out to me. It's an interesting because in LA if you say, “I'm a writer,” people are gonna assume you're a screenwriter.

Tracey: Mm-hmm.

There’s this feeling of being adjacent but isolated.

Tracey: Screenwriting, from my perspective, it’s a collaborative effort. You write something and then you take it to a team for it to be constructed. Like, the screenwriter essentially is writing the map, but then there's a director who's gonna be the captain to navigate it. And that director may take different turns and do something that's not necessarily on the map. Whereas a novelist, they are the navigator and the captain of that ship. They are completely alone in dictating the experience of the audience. So I wanted him to be more solitary.

And they’re alone in their successes and failures. Michael seems to feel that like very deeply.

Tracey: Yes, exactly. I felt like an author would synthesize the loneliness and also harken back to some of that old, Raymond Chandler, Philip Marlowe stuff, where you have this solitary man in LA and he’s trying to find something. So there's a bit of a Noir-ish angle. And maybe he's not a crime detective, but he is a detective of his own feelings and his own work. So I wanted to pull from all of that and a bunch of writers that I love from LA like Charles Bukowski, Fante, Eve Babitz. There's a whole lineage of these great writers who speak about LA lovingly, but also of the pitfalls.

I was writing down the titles of all the books that were popping up while I was watching, and I was thinking about Eve Babitz, who’s featured prominently and who talked about how LA is a place that’s inherently unserious. And she actually felt like that's the best part about it. You can't like it here if you don't know how to let go of yourself a little.

Tracey: There’s no permanent wins or losses here. I heard her once say in her writing that she could only operate either having a bunch of money or being destitute, but this was the place where both of those things coexist.

And it's interesting because Michael is somebody who takes himself seriously, that wants to take himself seriously, and that puts a barrier between him and the city.

Tracey: I agree. And to that point, I just finished the outline and am halfway done with this short story that I'm gonna make before the next feature. It’s about an East Coaster who's constantly talking down on LA, and we all know that person. It's called The Great Asshole of Los Angeles. It addresses those things. Like, there's a lot of people who come to LA really self-serious. And I don't necessarily believe that was me when I came to LA. I don't think I felt self-serious and I don't feel self serious now, but we have all encountered that person. They come to LA and they're like, “This is not like New York,” because of the bagels or the left turns or the pizza. I mean, Annie Hall, famously.

“Why would you go to a city where the only cultural advantage is being able to turn right on red?”

Tracey: Exactly. So that I wanted that for Michael’s character, but I also wanted to put him in a place that was foreign for me, in middle age or whatever passes for middle age. I mean, I could be middle aged now. I wanted to make him older than my own experience because I wanted him to be someone who had been in this state of taking himself so seriously for longer than he probably should have. Like he's been sitting in it for ten or fifteen years, in LA, but he’s made it his point to not enjoy his life. And he blames the city, but there’s something else he feels haunted by.

Yeah, absolutely. It’s in the opening sequence when he’s looking at the poster of him as one the best authors of 2010. Even just the world that he came up in is so lost, you know? It’s lost. It's not the Obama years anymore.

Tracey: Exactly, and that's what he's mourning. And I did put in places that I considered to be places we’re mourning in LA, sadly. Like, I put the Cinerama Dome in there. That's a great place of mourning. A cultural landmark, but it's been sitting vacant for half a decade. You know, just some of the beauty, but also relics that exist within the city. And I definitely love Los Feliz and Skylight Books, so I wanted to kind of curate a proxy of that so he could go there and, whether he knew it or didn't know it, he’s going to revisit a place that is exalting him. He's not going to a movie theater. He's in a bookstore, which is like his church.

So why was it important for you to have him to run into Fatima there?

Tracey: I think, for me, a lot of times people watch movies and say, “That could never happen, those coincidences don't happen.” But, when I live my real life, there's a lot of coincidences that seem so serendipitous you couldn't make it up. So I wanted something like that to happen because those things do happen. Like, people randomly miss a turn, and then there's an accident that happens there right after. But I did also want to create this mystery about Fatima at the bookstore. Maybe she's looking for Michael. Maybe she's not there for a conference at all. Maybe she's looking for him and she's heard he's an author and so she wants, in some way, to summon him.

Absolutely. I mean, that's an interesting about her character. It would almost be unsurprising to me if at the end she wasn't even actually there.

Tracey: You know, I just thought about the film in that way too. The whole thing could be a pure construction of Michael's.

Feral regret.

Tracey: Yeah, I think that’s a viable pathway for how to view the movie. And I made it in that way, you know, where the time is not as concrete. There's a lot going on in his mind. There's a lot going on that's kind of like emotional coloring. So I wanted to make the place they ran into each other like a place where she may be looking for him. Even if she wasn't looking for him, literally. She was like, “Well, I know his work might be here.”

It's clear what she means to Michael, but one of the things that makes her such a compelling character is it's not completely clear what Michael means to her. What do you think that meaning is?

Tracey: I think for both of the characters, the other represents some alternate path. And because it's a what if, it seems brighter. But even at the end, Fatima and Michael are idealized partners for each other, but it's clear that they don't work. There is a rhythm and a beauty to the reality of that.

Yeah, I mean, it didn't work the first time around.

Tracey: Exactly, and I think that's something that Fatima acknowledges in their final dialogue scene when she's like, “This weekend isn't real.” Like, yeah, this is something that we're doing, but I'm going home tomorrow to my real life. This is a pause button. What's really going on? She's dealing with her marriage and possibly the dissolution of it, or even just the difficulties that she expresses to Michael, and he's dealing with his own difficulties. And I feel like both of them represent a moment, to be honest, in a way that they weren't with their partners or about their lives. And you see it in the beginning of the film where Fatima was talking about her kids. She loves them, but then later on she’s like, “I don't necessarily want to just be a mom all the time.” And she’s terrified to do it by herself. So I think their relationship is a bit like an onion where, as their weekend goes on, the layers get peeled back until you see the real raw emotion.

I was struck with the idea that the weekend doesn't exist. Obviously she’s visiting and there is this sense of transit as something that distances, emotionally, and also somehow allows for more intimacy because of its impermanence.

Tracey: Yes, it is like you're creating this fictional world that can’t last, but is kind of like a stop gap in the real crises of your life. Both of the characters in Cassava Leaf are experiencing crises. And, to an extent, I show the Rochelle character experiencing that too, although she's not as focused on, but I wanted to show she's dismissive but she's dealing with her own things.

They're all well-rounded, even her for not being in it as long as the others. You empathize with all of them. Michael is portrayed very compassionately, but, for Rochelle, you also get the sense that he’s a person who would be hard to be with sometimes. Someone who’s always looking back.

Tracey: He’s the Great Asshole of Los Angeles. He's this guy that's always sulking and believes he's more serious than he actually is. A guy who imagines himself one way, and maybe he once was that one way, but he has not allowed himself to evolve internally to what his reality actually is. So he's kind of frozen in time, which is difficult for anyone to deal with.

How did you choose the books you feature in the film? It’s not just LA authors.

Tracey: There's a bunch of books, but I always try to make them a reference to what the films are, and this film, in its title and a lot of the themes, is an homage and an offering to my reverence for Yasujirō Ozu, who's one of my favorite filmmakers. He has this beautiful film called The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice, which is about this married couple and they're having friction and they go off with their individual friend groups and they kind of bemoan their spouses. But then they realize like, “Oh, my spouse is not that bad.” The woman is with her girlfriends and she’s like, “I don't want their lives.” And the guy meets an old friend who doesn't have a wife and he’s like, “Man, this guy is down bad.” So, then they come back at the end and they're like, “You know what? We got problems, but this works for us.” So, I wanted to pay reverence to not only that film, but to what I think Ozu does really brilliantly, which is paint the most beautiful pictures of the mundanity of life. He makes everyday life—you know, going to work, having a family, dealing with the angry boss, dealing with your daughter, getting married—he makes these things so beautiful and profound. You don't need the explosion. You don't need a knife fight. It's like, these are our lives. I don't know how many knife fights or explosions you've had in your life, but I've had exactly zero. As I get older, these films resonate with me. I feel more of a kinship with them because I can see my own life reflected in them. So, there's a Ozu book in there by Don Richie that I have, that I actually reference all the time, along with a bunch of other authors and books that I love. LA-based authors and books that felt really resonant to me. I love Bret Easton Ellis' essay collection, White. I included a bunch of Bukowski works, a bunch of Eve Babitz. I put in the great Eiko Ishioka. She has these really beautiful coffee table books. I've looked through them, poured through them so many times, and hopefully they've influenced some of my visual language, so I wanted to have that included. So, to me, I just love explicitly pointing out some of my references. Even to the point where you walk by the New Beverly—big shouts to the New Beverly—and you see Ikiru and Nanami: The Inferno of First Love, are playing, which are two films that I, one, love and two, feel like have themes that my film shares. And then on the posters you'll see In the Mood for Love on the wall. I try to put the breadcrumbs of what influenced me, so that people can be like, “Oh, what's this?” And you go down that rabbit hole and hopefully it gives you something like it gave me.

All art does exist in a tradition, in a lineage. That especially comes through with Michael's character when he’s passing by all of these books that you've just mentioned, and then going to his own book and picking it up. He's so in his own head that he walks past those people that got him into it in the first place.

Tracey: Yeah. And even like the Chinua Achebe book. I love the title of that book, Things Fall Apart. Because I think the character, Michael, feels at that moment like his life is falling apart. Which is not too different from Okonkwo in the book. One is about colonialism and one is about this upper-middle-class guy who perceives more slights than perhaps are actually there. But, I try to point to these things that I love. Hopefully, people will get it and if they don't, I feel like eventually they will, or the right people will. It's all there. It's in the film, just waiting to be discovered.

What movies do you think led you down the path to Cassava Leaf? When you were first getting into film, what were you into?

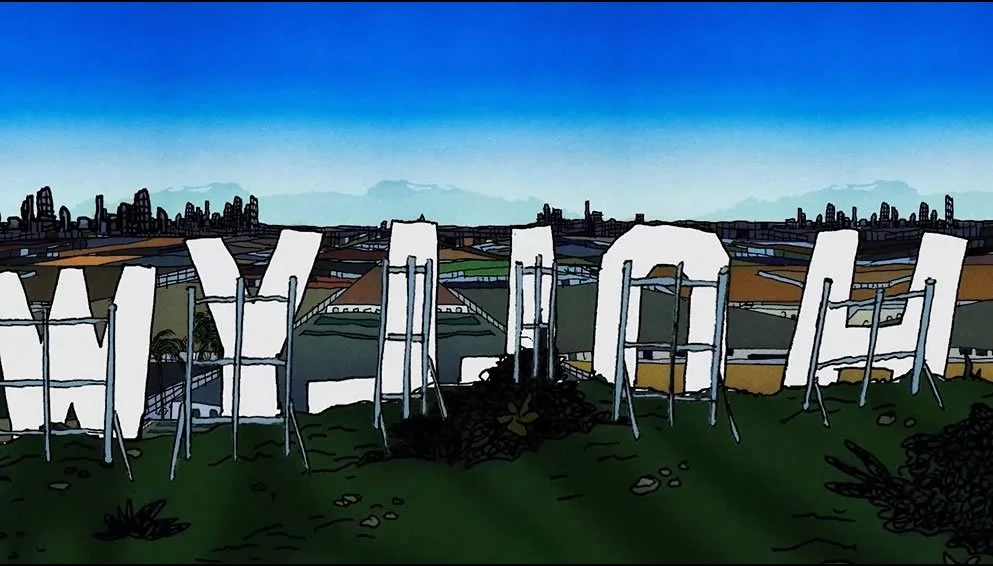

Tracey: I've always loved film. I’d put that first Ninja Turtles right up there with Mean Streets or Casino. I think there's something to be gleaned from all of it. So, when I first started to conceive of making my own films, I really looked at people like Ralph Bakshi or René Laloux. Some of Moebius’ collaborations with Laloux I really love, like Time Master. But in terms of animation directors, Bakshi and Laloux were the first ones to really open up my mind to what you could do with this medium in terms of making it really profound and resonant. Yeah. And then I saw films like Persepolis and went down that rabbit hole. I learned that it’s a medium. It's not a genre that's relegated to this tiny box. It's a medium to tell every type of story. Those filmmakers really spoke to me and it was just a matter of my friends, like Simone Films and the Ion Pack guys, really believing in my work and giving me that push to keep going and make my own films.

How'd you guys meet?

Tracey: Through the way that people meet everywhere today. We met through the Internet. Then we would work on things and then we would meet up in real life. And over time, as with any relationship, you realize that this is your community. You have similar tastes, similar principles. That's really how it started. We connected online, met in real life, and still liked each other. And, yeah, we've just been rocking since.

When you're working on something like Cassava Leaf or your next film, what’s the level of other people's involvement throughout the process?

Tracey: Oh, that's a beautiful question because I think both forms of work strengthen the other. So, working on other people's projects and being directed is great because it allows me to understand their vision, to understand how a piece works in the larger whole and to sort of curate my storytelling in that way. And then it helps me go into my own work. Which I write and then direct, and I'm writing it, I'm directing, I'm storyboarding, but it becomes extremely collaborative whenever I'm working with the composer. Most notably for Cassava Leaf, Will August Park, who I love. He's immensely talented and he's just a beautiful human being. A really good friend. And working with him, we built the foundation of the rhythm of the film. I have reference music and then I send him the references and I'll send him pieces that I've animated with the reference tracks. And then we'll talk about ideas. We'll talk about what's the emotion in the scene. We talk about what references we want and who would be a good collaborator for this portion. There were Bossanova references that I had at one point in the film, and there were other synth pop references. That’s all collaborative. Whatever I have as the reference music is never as good as what Will brings back to me. He brings a lot of it back. Like he's gonna bring you four or five different versions of each musical cue and you're just fine-tuning it and making it fit that exact piece. So that's extremely collaborative. Working with the actors is very collaborative because they also are bringing something to the film that I could not account for, in their performances. There are tapes where Armie—the lead actor who plays Michael—had an idea for the dialogue in the scene, about keeping it short. We did it both ways, but in the edit, I realized he's exactly right. The way he suggested his take was the best version of it. It taught me that you write these characters, but you pass them off to the actors and then they breathe life into it. They have a different and sometimes better understanding of the character. You have to flow with that to make the best possible project. There's a flexibility in allowing the actors to play in the work and bring their own experiences, their own ideas. Ultimately it's gonna make the work more natural. To me, natural is what you're going for. It all becomes very collaborative. And George [Twin Shadow] was an amazing collaborator. He gave a few different versions of the final song that we hear. He was so warm, so endearing, and a big advocate of the story. Once I sent him clips and the script, he was just really moved by what the story was saying. The world knows he’s a generational talent, but the way he tapped into the song, just through talking about what I was trying to convey, hearing the reference music, catching the rhythms of the overall themes. He was really a sponge for what the film was about and what was in the script. He reflected all of those things into the song. Even things that I didn't necessarily say outright, he gleaned those from the material. I was like, “Wow, this guy really is a genius.” And I would be remiss if I didn't mention Candace Leone, who is the voice that starts the film. She’s worked with Will for a long time. She came in and sang this really haunting melody. And she did it a few different ways, which I was so grateful for, because I wanted to hear it without dialogue, just with hums. She was so gracious as to do all of that. And what you heard in the film was her natural voice, which is so beautiful. It just fit the overall haunted tone of the film.

The opening song is gorgeous. It’s so timeless—I was sure it must be older.

Tracey: Yeah, it was written for this. The instrumentation is by Will August Park and the vocals are Candace Leone. And, man, it’s beautiful. You know, I look forward to working with all of these people going forward. It's a very collaborative effort. I'm always working to live up to what these people have so graciously lent me of their talent. So when they give me this beautiful music, these beautiful compositions, I'm like, “Okay, I cannot fuck this up now.” I have to do this justice, because these actors are in here really pouring out their souls. Will is giving me some of the best instrumentation that I've heard in the film. Candace and George are just like some of the most beautiful vocalists. George's whole composition was outstanding. So, I was like, “I have to do this justice.” Collaboration pushes me to do my best. I'm like, “Okay, I have to steer this ship into port now.” I have to make sure we don't end up on the rocks somewhere.

It’s creating within community. You have people that you become responsible to, that you're accountable to, because you've both given each other time and effort and so there's a reciprocity there. Like you said, “I can't fuck this up.” Because now there's a community around it.

Tracey: Absolutely. A lot of it is being a cheerleader and getting people excited about it, and maintaining that excitement and those expectations. You can't let them down. You’ve stirred up all of this interest and people have decided to believe in you. That's a lot of responsibility.

So, what does community in art mean to you? Why is it important to you?

Tracey: It's extremely important to me. I don't know if I would be doing this if my friends hadn’t pushed me and encouraged me to keep going. They gave me confidence in my own work. I had an idea of what I would do as a filmmaker, but then having my friends say, “You should keep doing this. This is sick. We want to see more.” It really gave me a lot of confidence to continue on my path. For me, I make art for myself. If I love the film, it's successful. I hope people see it, but ultimately in each of these projects, there's something cathartic that's happening that I need. I've done work for hire where there's a very clear script they want you to follow. The act of making is still cathartic, but you have less say-so in what the project is. So, it doesn't organically feel like your baby. It's like you're a surrogate for someone else's idea. But Cassava Leaf is my baby. It came from me and my blood, sweat and tears. I carried it to the finish line. and it was my Fitzcarraldo. It was me taking the boat over the mountain.

How long were you working on it for?

Tracey: The first person I approached in the collaboration was Will August Park, and that was December 2022. I think I had written it maybe a month before. I wrote it really quickly. There are 70,000 frames in the film. That’s over two and a half years, which you're doing in the middle of other projects. So, you really have to love it, to be honest. It would start and stop. So I would work on it, then I would get a gig that's maybe a couple months and I'd have to put it down. And then I'd work on it for another two or three months, then get another gig that's like four months. Those other gigs would help finance this thing. In a way it's a pallet cleanser too, to do the other work, because it allowed me to step away from this film.

Is it the longest thing you've animated up to this point?

Tracey: Yeah, 43 minutes. There's a grain to it. Each frame is a little bit different, there's a little bit static, it moves a little bit, which takes effort as well. There was some grain software that I was able to use. Another creative, Matthew Daniel Siskin, graciously passed it on to me. He told me about it and I researched it and it was exactly what I needed for the film. So I appreciate him pointing me in that direction. It’s such a delicate balancing game, weaving a narrative that long. I feel like I'm still learning. I'm always learning. You're keeping a narrative together for 43 minutes, trying to keep people's interests, trying to make sure it develops organically. I was juggling all those things. Making sure that it wasn't dead in certain places and the narrative still made sense. There were scenes that were cut out.

Did anyone along the way encourage you to keep those scenes in so that it gets out of the 40 minute zone and closer to an hour, hour plus?

Tracey: I won't say anyone encouraged me. I definitely had talks with my distributor, NoBudge, about lengthening it because it is such an oblong shape at 43 minutes. But, ultimately, they were super supportive of me making it what I felt was the best cut. That’s the one that exists, and they were behind it a hundred percent. They were like, you know, 43 minutes is peculiar for programming, but they're very creative-forward. They're like, “If this is the best cut, then this is the cut going out.”

43 minutes is a defiant runtime in film.

Tracey: You know, I have issue with some of the dogma in film. It's like, why does a feature have to be 90 minutes in 2025? It can be 40 minutes. If you tell a complete story, then 40 minutes can be feature length.

That's an interesting way to think about the difference between a feature and a short or a serial. Like, is it a complete story? If it is, then it’s a feature.

Tracey: Exactly, and I feel that way about watching stuff from the very early days of cinema, or if you're watching Tex Avery or any of that animation, they're showing you these Bugs Bunny cartoons that are like 12 minutes and it's a complete story. They would show those in the theaters like, “This is the movie. This is what a movie is.” And then, somewhere along the line, things became so calcified. Now a feature has to be 90 minutes or more. And we know why that happened. It was because of programming. It was because of money. It was like, we can program this many shows in a day. Yeah, it’s money. But I think, in 2025, everything is up in the air, really. So I don't think we have to hold fast to the things that were. I think it's actually a new time for film. I'm really inspired by movies today. Even as people decry the industry as falling apart. I'm really inspired by the films that I see. Whether it be Sinners, whether it be One Battle After Another, whether it be Him, whether it be Superman. Like, all of these films are wildly different, and they all are able to exist in this time. People are able to say what they want to say through their films. Like Weapons, too. All of these films people are able to make. And there's still independent films and there's the big studio films, there's micro budget films. I've seen films in each of those, air quotes, categories that are beautiful. I think Eugene Kotlyarenko’s The Code is one of the most relevant films of this year. I really love that film. It might be, in my opinion, the definitive statement on COVID. I don't know if I've seen a film portray COVID better than that. But all of these films exist today, so I feel inspired by film today. Maybe it's not a great time for the film business, but it's a great time for movies and for people who aspire to make movies. And that's how I feel: if you're willing to give everything that you have in pursuit of this thing, then people will support it in some way.

And you had this whole other life as a journalist and political scientist that you walked away from for film.

Tracey: Yeah. And, you know, that life, I feel more and more, has only strengthened my filmmaking and storytelling. It gave me experience and it gave me a viewpoint. And I'm really appreciative of it, because I still maintain that those are things that don't go anywhere. Like, you keep that experience. Your viewpoint evolves, but the experiences that I had before this, as a journalist and as a political scientist, I bring into every single project.

It brings me back to what we were talking about with unconsciousness earlier. When you're in the middle of something, it’s hard to see out. You know, 10 years ago, I'm sure you were just like, “Well, this is just what it is. This isn’t to any other end other than this end right here.”

Tracey: Which is so funny 'cause I didn't ever think that I would be sitting here with a film that's going to MUBI, that’s playing in different festivals. I just— That's not what I saw from my life. I loved film at that time, and maybe, in a way, I was a little bit afraid to get too close to it because I loved it so much. I didn't want to ruin that love as an audience member, but I guess it was to be.

In a way, you're sort of in the position opposite of Michael. Like, you're, you're looking back, you're 10 years ago is like something that like, you know, you're good at it, but you didn't necessarily want it.

Tracey: Exactly, yeah. I mean, there were definitely times that were unfavorable, but I didn't hate it. But I wasn't passionate about it either. Then once I was forced to evolve, through fate and through the encouragement of others, I think I was forced to evaluate: “What do I really want to use my time to do? What do I want to use my life to do?” And it was like, I'm a missionary. I wanna be a missionary of movies. Like, I'm using my time to tell stories because they are powerful, you know? Talking about Yi Yi, or Fitzcarraldo, or there's a film that I love called Les Olympiades. There's films that really move me. The Most Important Thing: Love by Andrzej Żuławski. Like, these films changed my life. They changed the way I look at things. Black Orpheus. Oh my God, that's one of my favorite films. I might fire that up today because it's such a perfect film. And from the start, you know how it ends because it's the story of Orpheus. It's like, we know this is a tragedy, but you go for the ride because it's such a fresh reinterpretation of that narrative and it becomes something new. So, yeah, these films changed my life and I'm honored to even be able to add to the thread of film as a medium. I hope that people watch my films and take something from them and then go make their own.

The Flavor of Cassava Leaf Over Rice is now streaming on MUBI. You can also see it at The Roxy in New York’s Downtown Festival on Sunday, October 12, at 10 PM, with a Q+A moderated by the film’s composer, Will August Park.