[INTERVIEW][11/20/25]The body is a container

A Conversation with Alex Moreno

It can be a terrifying prospect to simply exist. We are given these bodies, and they are destined to betray us. We are tethered to time, and that will betray us too. In fact, the two will work together. But there is another way to look at all this—one less steeped in the horror than in the wonder of our experience.

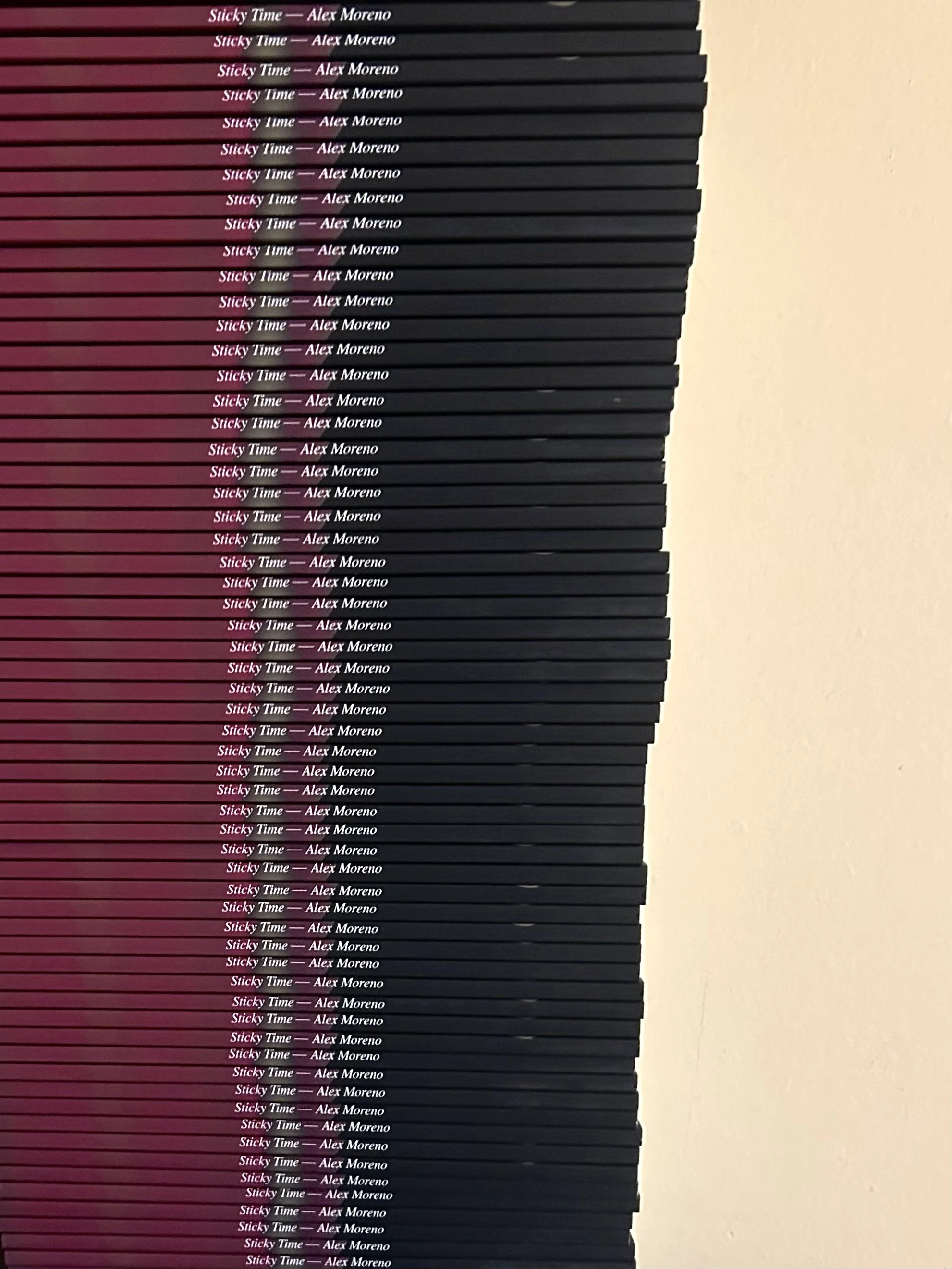

Sticky Time, the debut collection of poetry by Los Angeles writer Alex Moreno, was released on November 15 from Sunflower Station Press. It opens with a one-line poem, “Another I pulsed,” which reads, “When this started, a year ago, in the middle of an operatic summer.” What follows is a treatise on time and the body, and their relationship both to our everyday humanity and to God. It could be lofty, unapproachable, if it was more concerned with finding answers. Instead, Sticky Time is a sandbox in which Moreno takes these ideas and forms them into more playful shapes. God is infinite but gentle, the body is frail but astonishingly beautiful. And time, too. Time is moving but sticking to everything.

I sat down with Alex to discuss the book and her personal relationship to all of these concepts:

One of the things that stuck out to me the most is how much of Sticky Time has to do with the fact of the body. Like, our bodies being the only things that truly ground us in anything. So, as you were writing these, where did the body figure and how you were thinking about it?

I think at the beginning of writing this book, I was in a very bad place with my body, stemming from the fact that I was having an eczema flare that was the worst I've ever had in my life. So I was very hyper-aware of my body, and was using the poetry as a way to dissect it and make it absurd and sort of hold this magnifying glass to it. That felt like some form of control. And I think because of that too, I was hyper-fixated on the systems of the body. I’m fascinated by biology in general. I think it's very divine and I think that the history of medicine, like anatomical drawings and anatomical dissections, was a way for early modern thinkers to understand and quantify the divine. And I’m also fascinated with God—there's a lot of God stuff in the poems too—and the body is a physical manifestation of our divinity to me. We experience the world through these bodies. And this collection starts in a very scattered, manic state, because I was struggling both physically and emotionally. I was desperately searching for answers in the body, desperately asking, Can you show me how to heal myself?

I was also struck by the motif of nails falling off, which shows up frequently throughout. There’s so many ways that our bodies betray us. How were you reconciling the divinity you saw in the body with this betrayal that you were feeling?

Yeah, I mean, God creates and God destroys. I think we get the full experience in the body and it's not always going to be your friend, but I think it is always a part of you. The nails became symbolic of the body being separate from the self. Like, what changes when you peel off a fingernail and leave it somewhere? Am I leaving a part of myself? I think in the poem it's a different country. I leave a fingernail on the way to the airport and I'm like, Oh, is that a way of marking my territory? And again, taking back control.

It's like carving your name into a tree.

Exactly. Scattering pieces of myself everywhere.

All this talk about God leads fairly easily into talking about time. So many of the poems also have to do with time. It's interesting because the body is such a physical thing in the poems, but time is less solid. I’m thinking of when you say something to the effect of, “If I know you in the future, have I already met you?” I'm just interested in what you saw as the relationship between the two. When we think about our bodies, it's usually so related to time in the concrete. We almost think of our bodies as existing in relation to time more than anything else about ourselves. But you treat them separately, and you seem less afraid of time than the body.

To me, time is a very playful thing because time is a concept. I know that my body experiences time linearly, and that feels like a fact. But in the bigger picture, as a philosophical concept, time feels so pliable and uncertain. To me, that makes it exciting. It’s so unanswerable in a way that doesn't really affect me in the same way as my body and the questions that it raises when it's betraying me. That's a very immediate experience versus questions of time and questions of God. Those are questions that I'm never actually going to get answers to, so it becomes this play space where I can be like, Oh, what if I’m accessing the future when I'm meeting someone? What if me at ten-years-old is in existence out there and just doing her own thing? That just has more levity to me. And I think also accepting that the body faces mortality, then there's the question of the soul and the soul being infinite and something that's out of time. Which feels also like the acceptance of God, which is something that is greater than time.

Photo by Anastasia Duchess.So you believe in a soul.

Yeah.

How do you feel the soul relates to the body? Is it necessarily tied to our body, or is it something that extends beyond our body?

I think right now, my soul is in my body. But I don't know what happens when I'm sleeping. I don't know what happens when I die. I don't know what happened before I was born. I think that's the myth. That's the mystery.

It's interesting you say mystery because that's another thing I wrote down while I was reading. The way you treat time and God is so playful, but it acknowledges this much larger mystery to all of it that could be seen as serious. Like, it’s definitely led to some panic attacks.

Definitely. I mean, big questions are cause for big feelings. But I feel like I’ve been at peace with my conception of God for the majority of my twenties. And it hasn’t been tainted by a religious upbringing, which I think is also really key.

So you weren't raised religious?

No, which I think makes for my healthy connection with God. I know so many people have difficult childhood experiences with religion and that can influence what their relationship is with God. I feel grateful that my parents—they both came from different religious backgrounds—they were like, Okay, our household is not religious. And I think that's cool because then in my early twenties I was able to come to it with my whole childhood and adolescence experience clean. Clean and able to read about spirituality and different ideas about God and these big concepts with a more formed self. I mean, when you're in your early twenties, you're not exactly fully formed, but you’re more formed than a child. And now I'm in my late twenties and I feel comfortable in my belief systems, and because of that I can play with it from a point of view that feels solid.

How did you come to God in your adulthood?

A little bit of everything. Philosophers, mostly. Emerson was a big influence, especially his essay “The Over-Soul.”

The way that you write about God in this made me wonder if the Transcendentalists had something to do with it.

Yeah, definitely. Walt Whitman, too. I mean, I went to a summer camp for 10 years called Camp Walt Whitman. So it is baked into me. And honestly spending lots of time in nature too. I went to college in Maine and one summer in-between school years I lived on campus and had an internship and was just in the woods, by the water, hanging out with my friends. And it was like paring back of everything in my life. I didn't have school stress. I had no worries. I was in vacation land. And I was like, Nature is God. Something made this. That's kind of where it came from. It came from looking at how big nature is and thinking, How? These ridges in the mountains and the branches on the trees are like the veins in my body. Everything is so similar. There's so many patterns in nature that I felt, There is one creator here. And also the miracle of the body. The miracle of a properly functioning body to me feels very divine. It feels like this is all ordered.

I think it's interesting because there's this sense of—especially the poems that deal with love between people—our bodies being the only thing that's stopping us from coming together as one thing. It's a very transcendental idea of, I am you. We share parts of the same soul. It's just separate parts. And in your poems it feels like you’re taking that idea and saying, We want to just melt into each other, but we have these bodies.

I love that image. Yeah, the skin is a barrier to accessing the oneness of it all. The body is a container. The body is what makes it so we're not all spilling out. So we're not all the same and unified. But while we're here, we get to just play around in these things.

Photo by Clare Schneider,Why did you choose to open with the one-liner poem?

I started with that because I wanted to ground the book in place and time. It starts in the summer a year ago, and the poems are pretty linear in terms of narrative arc. I wanted there to be this structure of the speaker going from being emotionally unwell to emotionally and physically grounded and stable. And I think starting it with that one line poem grounds the book. It’s like having the speaker name herself and say, Okay, this is where I'm starting this story, and then where we end is a completely different place.

I think that's interesting because you play so much with the idea of beginnings and endings but you also say over and over again that time isn't real, or at least not real in the way we typically think about it.

Well, I'm not a time-denier by any means, but there is this concept of Eternalism. It’s the concept of past, present, and future all existing at once and us just not being able to access them all at the same time. We can only really access the present. Unless, of course, through memory or deja vu or if you have psychic experiences and those structures slip. When you have deja vu or a premonition, time gets dislodged. There are so many ways to dissolve the barriers of time, I’ve learned. Our consciousness is so limited. Our brains create these structures to keep us sane. But I think at moments of high distress or even going through a mental health crisis, your brain gets all shaken up and those barriers dissolve. Then weird shit happens.

You treat our relationship to time similarly to how you treat our relationship to our body in that both are our containers, or the ways we understand ourselves and our reality. And the thing that prevents us from truly being able to be together is time. It’s what gives us beginnings and endings, when nothing really ends and nothing really begins.

Exactly. I know, and it's kind of scary but it’s kind of comforting too. If you really believe that there is no such thing as a beginning or an end, then I think it can be a very blissful existence. You're just in perpetual acceptance. Things happen and you just keep going. There's no way to know what anything means. You could have met someone five years ago and think, That's the last time I'm ever gonna see that person. But then five years from now, you see them again, connect, get married. But at that point in time in the past you thought, That's the end. So I think you really don't ever know what's going to happen.

Does time move quickly or slowly for you?

It changes, poem to poem.

What about in your life?

Does time go quickly or slowly? Depends on the day, the week. But it is interesting, yesterday I was like, Oh my God, this week is going by so slowly. And then my roommate was like, No, this week is going by so fast. I can't believe it. And that’s the thing: it's all relative. There's no objective experience of time. I think the speaker in the poems wants time to be quicker than it is at the beginning.

The note I’m looking at just says, Time and immediacy. Immediacy comes up a lot too—this exuberant immediacy. And I think we usually associate immediacy with impatience, but it's not that. It's more that has to do with you wanting to be able to sample as much of life as you possibly can. It's tactile. You have all these textures in front of you and you want to feel them all, but you only have an hour.

Exactly. It's this desire to experience everything, and know everything. I think that immediacy is related to the body and the body's fear of death. And I think that then gets passed on to the brain unconsciously. It's like, I need everything now. I need to use this body to know everything and I’ll know everything by touching everything, smelling everything, meeting everyone, reading every single book there ever was. And I think that's really overwhelming. That makes for some of the more manic poems in the book. This screaming, Oh my God, I'm only one person and I wanna have infinite experiences, but I only have this one body for this set amount of time.

INTERVIEW BY AARON BERRY DAVISPhoto by Patrick Zettle.ALEX MORENO'S work explores emotional processes through surrealism, visceral interiority, and synesthetic play. Sticky Time (Sunflower Station Press) is her debut poetry book. You can also find her writing in Spectra Poets, Lit Angels, and Dream Boy Book Club. She earned a BA from Bowdoin College, eats 1-2 apples a day, and really likes it.